Miniatures Featured in The Duel by Filmmaker Sean David Christensen

| Website | Instagram | Facebook | IMDb |

Tell us a bit about your work with The Duel. What’s your inspiration behind this piece?

Tell us a bit about your work with The Duel. What’s your inspiration behind this piece?

I was drawing at my desk late one night, almost seven years ago, and I remember the tip of my pen hovering about a quarter of an inch above the paper, because I couldn’t move. I was frozen in my chair, completely engrossed in Lili Taylor‘s story, The Duel. I had just started listening to Kevin Allison’s RISK! podcast earlier that year, intrigued by its presentation of true stories laced with elements of suspense or tension. Lili was one of the guests that evening, and being a long-time admirer of her work, I leaned in closer to my laptop’s speakers. And that’s when I froze. Her slow unveiling of her experience as a sixteen-year-old girl struggling to reach her father in the midst of a mental crisis was so elemental and resonant for me, that immediately after listening to it, I dropped what I was working on and began sketching the storyboards for what would become the film that same evening.

As a live storyteller myself, I was inspired by Lili’s courage in telling such a personal and heartfelt story, and I wanted to honor the risk she took with my film version. Stories are fragile things, especially ones that have been guarded within our minds against all efforts made to erase them. After hearing the gravity in her voice, I knew this was an important story that meant a lot to her, one she chose to remember after all of these years, and one that I chose to bear witness to, as if it were my own. I too, would come to guard my film against my own doubts and fears about how I was going to complete it, for years, in fact. It was only until I realized that in order to fully realize my vision, I’d have to radically disassemble my original idea for the film and rebuild it, on a much smaller scale. That’s where the miniatures came in.

How do miniatures play a part in the film?

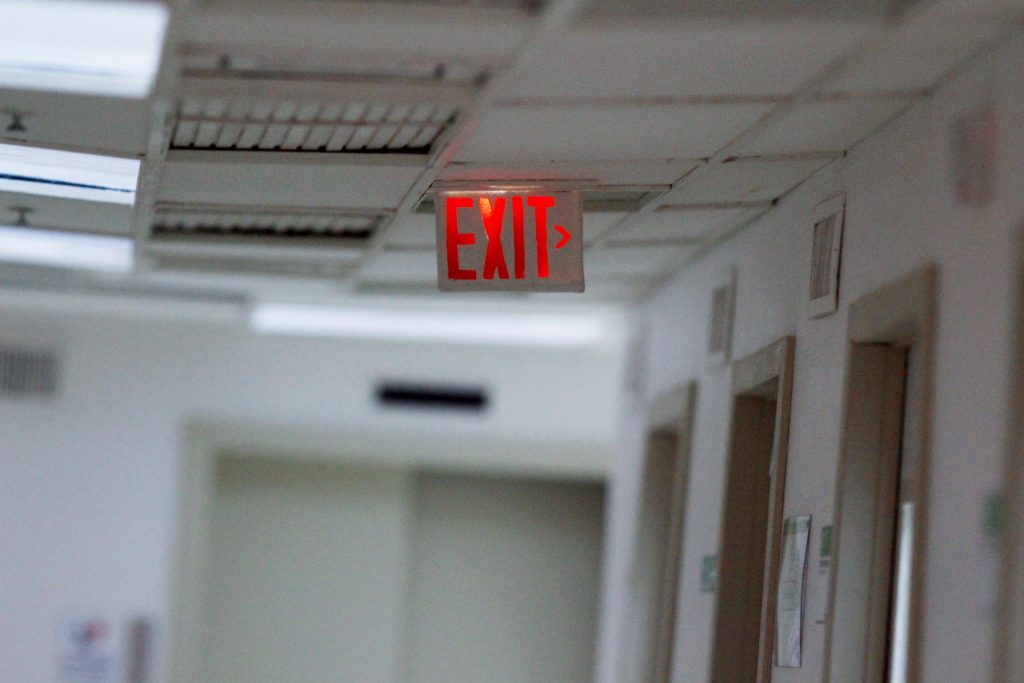

When I returned back home to Phoenix to be closer to my family, I brought with me a half-finished film that was missing key shots that required specific locations. Namely, I needed a pale green hospital hallway from the late 70s, a cavernous basement and the exterior of an old house with a wooden porch. After realizing it was going to cost too much to secure and film these locations in real life, not counting crew, insurance, transportation and food, I admit I became more than a little depressed at the thought of abandoning this film. While I purposefully avoided the folder my project was saved in on my computer for years, I struggled with how was I going to finish it. I couldn’t make eye contact with it. But late one night, sitting in my mom’s kitchen, I asked myself: “Why does it have to be real life? Why can’t my film swim between two worlds, large and small?”

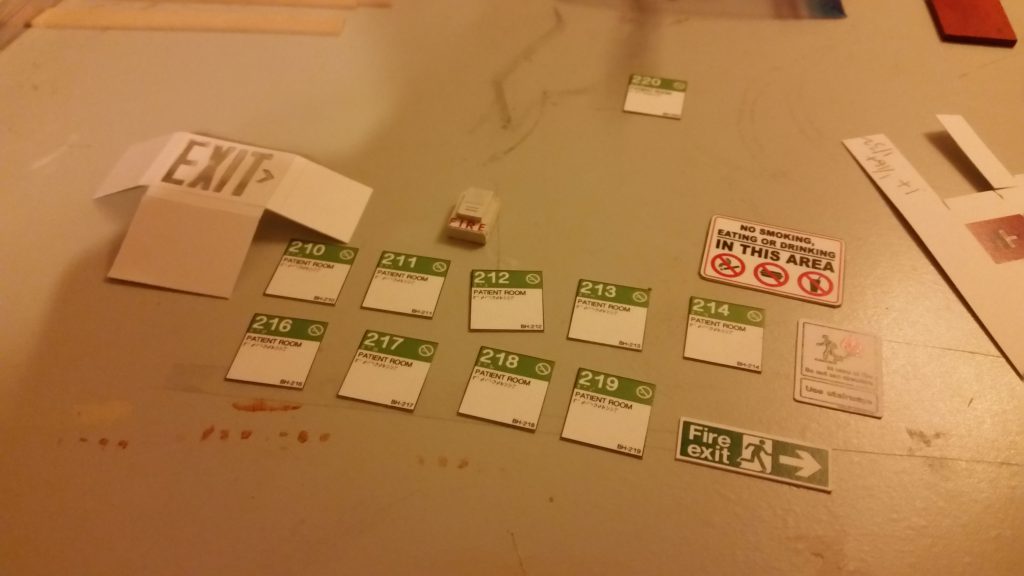

The three miniature sets I created for the film represent formative childhood worlds that Lili’s story drew from. They were all crafted with a level of detail that made it crystalline, like a preserved memory, but skewed slightly, as if unseen forces are squeezing their walls from the outside. One of the most compelling elements that originally drew me to Lili’s story was her sense of place, of the hard edges that defined the vulnerable state her father found himself in when she was young. Each building represents a facet of that tenuous connection to sanity; The hospital that cared for her father, the home that sheltered his illness from the outside world and the basement that transmuted itself into a bottomless pit of dread, where The Duel would take place.

The three miniature sets I created for the film represent formative childhood worlds that Lili’s story drew from. They were all crafted with a level of detail that made it crystalline, like a preserved memory, but skewed slightly, as if unseen forces are squeezing their walls from the outside. One of the most compelling elements that originally drew me to Lili’s story was her sense of place, of the hard edges that defined the vulnerable state her father found himself in when she was young. Each building represents a facet of that tenuous connection to sanity; The hospital that cared for her father, the home that sheltered his illness from the outside world and the basement that transmuted itself into a bottomless pit of dread, where The Duel would take place.

The obvious parallels to dollhouses and childhood were not lost on me either, as Lili’s story is told from her point of view as a young woman. But a dollhouse can serve a larger function to a child than a purely ornamental and nostalgic one. Some of my most vivid memories are of creating soap operas with my sister and her Barbies, spinning the combustible, adult world that surrounded us into tightly-wrapped worlds we could control. Family life outside her bedroom door was chaotic and disorganized at times, but the plastic cabinets, boots and purses were like charms we’d collect to make it all smooth and clean. To a degree, the miniatures in my film behave in a similar way, in their attempt to rebuild and make sense of the frightening debris of a single afternoon in someone’s childhood life, debris that continues to scatter into their present.

What materials, tools, techniques were employed to get these miniature sets up and running?

What materials, tools, techniques were employed to get these miniature sets up and running?

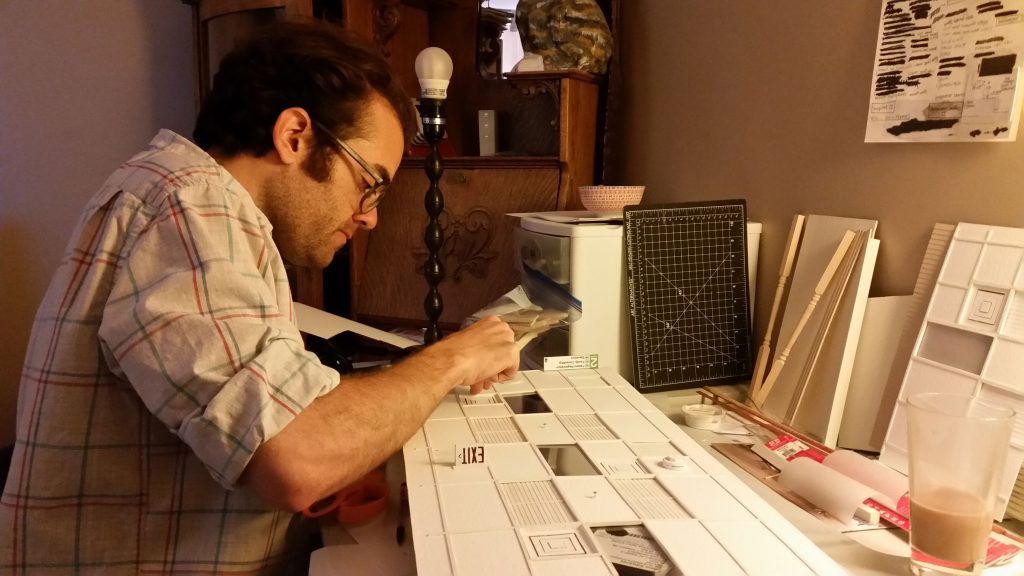

I didn’t have access to any power tools at the time, so I used materials that were able to be cut by hand. To that end, I cut the walls from balsa wood with an XACT-O knife and reinforced them with foam core using Loctite super glue as a binder. I used an 1/8″ scale ruler and eyeballed everything from reference photos, jotting down lots of notes and reminders to myself, like, “Light panel is 1/8 + 1/16th + 1/32nd inch wide with 1/16th wide switch.”

Everything took twice as long because I was teaching myself how to build miniatures while sawing away at them with tools that were definitely, in hindsight, not meant for how I was using them at all. I don’t recommend cutting dowels with a craft knife, but it’s all I had, so I just had to sit down and do it. Being Irish and stubborn definitely didn’t hurt.

What went into making the miniature sets you created?

The hospital hallway was built from the dimensions of a 1/12-scale Houseworks dollhouse door, three inches wide by seven inches tall. I laid it flat against some 4×4 graph paper and sketched out its orientation to its surrounding architecture by comparing it with Google image search results of similar hospital hallways. Once I got the proportions down on paper, I translated them into three-dimensional form with miniature elements that were analog to real world materials. For example, to simulate the tiled, popcorn ceilings you see in old office buildings and airports, I used 1/8″ wide strips of basswood for the grid and squares of 300 lb. Arches watercolor paper for the drop tiles. The paper had a rough tooth that caught the light and gave it just the right amount of grain when photographed. The light panel effect was achieved by simply leaving gaps in the watercolor paper lattice work and taping Walgreens brand plastic wrap behind them. When I shown light down through its waxy texture from above, it diffused the beam and softened it up, simulating a fluorescent glow.

Did you use any after effects or editing software to get the appearance of a real-life set?

Did you use any after effects or editing software to get the appearance of a real-life set?

Everything was done in-camera, and I actually made efforts to slightly distort and bend the film’s sense of reality with the way the miniatures were constructed. For the basement, I implemented an old theatrical trick, using forced perspective to narrow the steps leading up towards the doorway, making it feel more claustrophobic and far away. You see these techniques a lot in German expressionistic films like The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari and Metropolis, where the set designers impose a sense of oppressive dread by diminishing the proportions of the actors — all done with an imaginative sense of scale.

I built 29 steps, an unnaturally large number of stairs to have in any normal basement, and cut them against a 80 degree angle, making them widen by about 3/8ths of a inch each time they step down. By comparison, the top step is three and a quarter inch wide, while the bottom step is almost ten. The tightening of the walls up this column of seemingly endless stairs works as both a means to enforce a sense of childlike perspective, and communicate its accompanying level of panic. In Lili’s recollection, the basement serves as an ersatz stage for her father’s manic fantasy of a life-or-death “duel” to play out upon, taking place beneath the floorboards of the house like a terrifying secret. As a filmmaker, I felt it necessary to create a physical representation of that dark, imaginary place, uncontrollably winding down at the mercy of uncontrollable forces.

What is the most challenging aspect of your work with miniature sets and set design?

What is the most challenging aspect of your work with miniature sets and set design?

The most challenging aspect of working with miniatures is reconciling the weight of hours that get devoured by the smallest of details: door handles, light switches, screws, buttons — they all seem to accumulate and slow down momentum. It’s easy to look up at the clock and feel deflated after you’ve spent an entire afternoon creating work that can only be measured in inches, sometimes less. But it’s those same details that solidify the reality of a room or environment you’re trying to miniaturize. That one tangled extension cord or wadded ball of tissue paper can make all the difference. The immeasurable obsession of picking apart fractions of inches that may or may not be noticed is something that continues to frustrate me, but I know it all serves the larger picture. I choose to approach it this way: If you think of every detail, regardless of size, as being a load-bearing one that the structural integrity of your set relies upon, it becomes very easy to devote the time needed to make that detail the strongest it can be.

Why use miniature sets in filmmaking?

Why use miniature sets in filmmaking?

I see my films, primarily the experimental documentaries I’ve incorporated miniatures into, as tense relationships between the present truth and an idealized past. Our own personal histories, whether they serve the will of an elastic narrative we’ve written for ourselves, or the rigidity of memory, are shaped by what we command ourselves to remember or pray to forget. Just as editors cut loose ends from stories that sag, we too, are curators of memory. I’ve chosen to shape these memories into miniatures, and it intrigues me to use them within the grammar of documentaries to tell stories.

Traditionally, your camera observes subjects with passivity, complementing their words with some historical footage or photographs. It can be a little like sitting in a classroom, sometimes. I believe I’ve chosen small-scale environments to dislodge that authoritative role of the interview, and in its place, create a subjective type of musicality from their experience. Experience that can be interpreted a multitude of ways depending on who watches or listens. For instance, when a subject’s words are placed within a surreal setting like a miniature world, they seem to float, because there’s nothing familiar on-screen to hold them down. The audience, reflexively, has to cling tighter to what they hear because their sense of equilibrium evaporates. Nothing on screen makes sense, so words have to make up the difference, and that sense of authority is gone. My goal is to achieve that same sense of disruption, and for the audience to constantly question the truth of what they’re seeing, just as we question the veracity of our own memories. Like, “Did that really happen the way I remember? Or was it a dream?”

What advice would you give to new filmmakers?

There’s only one you, so don’t waste your time telling a story that can be told by just anybody. Tell the stories that can only be told by you. Ignore every impulse to leave out the details that might seem embarrassing or too revealing, because those are the only details that matter when it comes to storytelling. Time whittles away everything that’s unremarkable, leaving only the jagged bits that can’t be defined or predicted, the bits that refuse to be forgotten. Those moments, happy or sad, weird or terrifying, are worth it. No matter how long it takes you find them.

How can miniature fans view scenes from The Duel?

How can miniature fans view scenes from The Duel?

Those interested in The Duel can learn more about it at duel-film.com. It’s not currently available online, but it’s touring film festivals nationwide, and will be coming to a city near you, perhaps! Next up is the Marfa Film Festival from July 12-16. In the meantime, you can also listen to more captivating true stories like The Duel on the RISK! podcast, which makes a great companion for late night build sessions. Who knows, one of its stories might just inspire your next project, like it did for me!

Filmmaker and miniature set maker Sean David Christensen is based out of Phoenix, Arizona. To learn more about his film, The Duel, check out this website and IMDb. Make sure to follow along on Facebook and Instagram.